a Jules Vernes-ian adventure for modern mystics

Two years ago, I re-read The Chronicles of Narnia for a book club. And while it still has some wonderful images, Narnia disappointed me this time around as sloggish at times, and even occasionally off-putting. A mostly-absent God who only visits Narnia every few centuries now seems more deistic than Christian, the total separation of creature and Creator seems myopic and dogmatic, and its disinterest in peacemaking and justice betrays a missed opportunity.

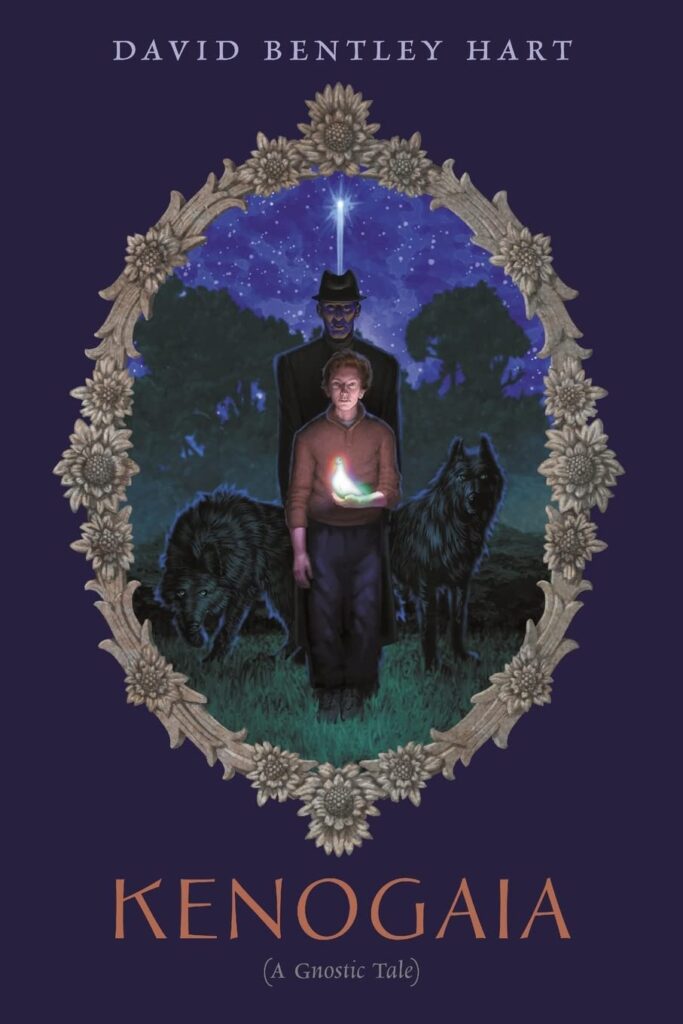

This time, decades after I had left my youthful Fundamentalism behind, I wished that Narnia had a deeper spirituality. Fortunately, David Bentley Hart’s Kenogaia (A Gnostic Tale), seems to fit that YA-spiritual-adventure space in my heart much better than Narnia now.

Kenogaia is the world where 13-year-old Michael Ambrosius is growing up, a fantastic realm reminiscent of a Jules Vernes-ian Europe, but with distinctive and otherworldly technology. Electricity remains undiscovered and land travel is limited to carriages, but manipulation of wind, air, and minerals has resulted in “anemophones” which enable people to speak across distances, aerial barges for travel and transport, and “phosphorions” give artificial light, among many other inventions.

By far the most different feature is Kenogaian astronomy (“ouranomony”); not only do its people believe that the moons, sun, and planets travel across the sky in transparent spheres as we used to imagine, but they know it as a simple fact: Kenogaians can plainly see the gears that move the spheres, and so praise the “Great Artisan” for his handiwork, broken sprockets and all.

The story opens with Michael’s father confiding to his son a seemingly impossible discovery: a new star is rapidly approaching Kenogaia. Given the nature of the spheres, this cannot be, but his illegal telescope confirms his observations, and he charges Michael to keep this discovery strictly secret, since in Kenogaia, knowledge and belief are controlled by an authoritarian fusion of science, religion, and psychology, and those who diverge too much from established thinking live in dread of being imprisoned and subjected to the horrors of “therapy.”

That same evening, Michael’s father is arrested, and soon Michael learns that the “star” is bringing a mysterious visitor to Kenogaia. This visitor, Oriens, appears as a child from an even stranger world. Michael and his friend Laura commit themselves to protecting and aiding Oriens while they also search for Michael’s father and Laura’s parents, who have disappeared fleeing the authorities.

Hart’s novel is loosely inspired by a beautiful poem, The Hymn of the Pearl, found in The Acts of Thomas, an early gnostic Christian writing (not to be confused with the Gospel of Thomas). A flowing translation of the entire poem (presumably by Hart himself) is presented as epigraphs for the major parts of the book. The Hymn of the Pearl tells of a child’s journey to a strange land to seek a stolen, priceless pearl and return it to his homeland. Hart skillfully uses the essence of the journey as foundation of the plot, and avoids the temptation of trying to use Pearl too literally.

Kenogaia‘s spirituality resonated deeply with me, and some images are going to inspire me for a long time. I believe anyone already on a mystical path will appreciate the rich and profound spiritual themes here.

But Kenogaia is not at all dry. Hart’s wit and humor counterbalances the adventure in delightful ways. A comical police briefing made me laugh out loud, and reminded me of Monty Python at their best. Hart uses his vast vocabulary to skewer villainous and arrogant authorities to great effect. Those who are familiar with his command of arcane words from his lectures and interviews might wonder if this truly is “a young adult fantasy novel,” but anyone who’s cultivated a love for reading science-fiction or fantasy, young or old, should be able to surf the sentences, and many readers will find the language as delightful as I did.

That said, Kenogaia does have some flaws. Two minor nits are that Michael seems too mature and eloquent to be a thirteen-year-old (their years resemble ours), and Laura has very little to do.

That I feel Kenogaia needs more editing is a different matter. Its 420 pages are printed in a smaller-than-usual type; it would be about 500 pages in a more typical size, and its story does not support that amount of verbiage. Many huge descriptive paragraphs could be trimmed. And overuse of cross-cutting in describing action scenes often fragments them to confusion, inundating the reader with tsunamis of detail. Editing—that dying art of eliminating the good to illuminate the best—could turn Kenogaia from a delightful experience to an unforgettable one.

But in spite of these quibbles, I read Kenogaia in a few days, and actually found it hard to put down, which I haven’t been able to say about any fiction I’ve read since I read Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash last year. Kenogaia is simply compelling, and it satisfies like a great first meal at a new restaurant. I hope this book finds much wider readership. If you like spiritual SF, you’re going to enjoy Kenogaia.

DBH, if you’re reading this, thank you for your beautiful work. May this “pneumatagogue” fly!

Kenogaia (A Gnostic Tale) David Bentley Hart, Angelico Press, 2021