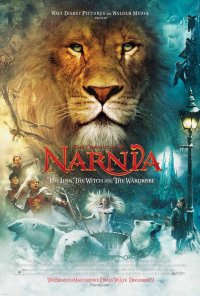

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

Fairy tale or fantasy?

I’ve got to say that I wasn’t terribly impressed by Narnia. That’s not to say that Disney’s The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a bad movie—far from it—but it isn’t a great one, either. In all fairness, Narnia was a most risky endeavor to bring to the screen for a number of reasons: its adult fans have a nearly religious devotion to it, and its stature has grown in their imaginations through the years, turning it into a mythic story it never dreamt of being. Deviate from the book, and the wrath of those fans will rain down upon you. Don’t deviate enough, and you’ll end up with a tale that’s as unassuming as the book they think they remember. It’s a Catch-22.

Director Andrew Adamson (his name translates as “Man, Son of Adam”—got to admit that’s cool, huh?) managed to slide between those two dangerous possibilities, and instead created a film that wants to have it both ways—a heroic adventure on one hand, and a charming fairy tale on the other. It’s more successful on the fairy-tale side.

The scenes of the children in England are quite believable, and the two youngest kids, Georgie Henley (Lucy), and Skandar Keynes (Edmund) are simply brilliant in their roles. However, the screenplay never quite draws us in. We never feel they’re in danger, whether bombs are falling around them in London, or if an evil witch is pursuing them. I would’ve liked more time seeing their characters developed. James McAvoy, who gave us one of the best perfomances ever as Leto in Children of Dune, has a pitch-perfect performance as the faun Mr. Tumnus, and his scenes with Lucy are probably the best in the entire movie. William Moseley (Peter) and Anna Popplewell (Lucy) are under-used, and at 18 and 17 respectively, they may soon become too old for the following movies. The White Witch (Tilda Swinton, fresh off her role in Thumbsucker) is deliciously evil when we meet her, yet we there’s some disappointment in entering her unimposing castle.

Springtime for Aslan and Narnia

Things further slide when spring comes to Narnia. Yes, you’ll believe that beavers and wolves can talk, and Aslan is beautiful and majestic. But his camp is a collision of gaudy red-and-gold tents and costumes, without a hint of dust to be found. The land ends up looking like a garish painting, not a place where a lion might leave his tracks upon the soil. Although it is a children’s fairy tale, Lewis told Narnia with humor, passion, and depth, which are all in short supply here. The kids barely react to their fantastic surroundings in Narnia, so we don’t either. Furthermore, in spite of their call to ascend the Narnian thrones, there is no believable transformation going on. A couple of brief scenes are supposed to show the children training to become warriors, but the shots of kids awkwardly swinging around heavy swords are just embarrassing. Without human adults in Narnia, who’s going to teach these kids martial arts? The beavers?

Lewis described the battle against the White Witch in a couple of short paragraphs. Here, it’s like a diet version of a scene in The Lord of the Rings; for the children it has to be restrained and it is, but for adults, it’s awkward and long, all which raises the question of why it needs a massive battle scene at all. And it’s a zoological mess. Polar bears, leopards, minotaurs, and phoenixes fight in the same scene. It’s as though everything a kid might like is thrown into the mix, just to be sure. Pour in the menagerie and turn on the blender.

I’ll say little about the spiritual symbolism of Narnia, since entire volumes and dissertations have been written about it. Yes, the symbolism of the book is still there, Aslan still dies, resurrects, and forgives. However, I winced at the scene in which Peter gives the battle cry For “Narnia and Aslan”. Enough of that. Enough of war “for Jesus,” “for Allah,” “for [insert divine name here]”. Sure, the battle is “not of this world;” it’s about the spiritual war, the struggle within our souls to become like Christ, united with God. But now and throughout the ages, we have projected our neighbor as the enemy, instead of our own lack of love. Peter’s battle cry doesn’t help clarify things for those who confuse them.

I like Lewis as much as the next guy, yet I think it’s sad that so many Christians can’t see the spiritual reflections in any stories but these, when so many stories, intentionally or not, are packed with symbols of spiritual sacrifice, resurrection, and redemption, and often of a much subtler and higher order than this; e.g. The Matrix, Pleasantville, and Spider-Man 2, to name just a few. (If you haven’t already, I encourage you to check out Hollywood Jesus. My friend David Bruce taught me how to look at contemporary film with a spiritual eye, and chances are excellent he can do the same for you.)

From what I’ve read, although they were close friends and Lewis admired Tolkien’s Middle Earth, Tolkien disliked Lewis’ creation, finding it a jumble of beasts and magics with no rhyme or reason other than allegory. There’s little sense in it. Why does Narnia need not one, but four monarchs to govern it, when there’s no governing to do? And both Cair Paravel and the Witch’s castle are so empty they seem little more than places to display thrones. In the books, these aren’t problems at all, but simply exercises to use our imaginations even more as the charm unfolds. Yet after $150,000,000 has been spent on the film, I find myself wishing for more depth and plausibility.

Adamson could have done better, but largely the problems are with the source material. The best Narnia adaptaion might have been to leave it very much the children’s fairy tale, full of charm and rich, grandfatherly voice-overs from the narrator, but in the age of The Lord of the Rings, that would be an unlikely sell. And turning it into a convincing world where good and evil are fighting to the death would distort it beyond recognition. Still, it’s not a bad attempt—but a somewhat disappointing one.

Movie stills © 2005 Walden Media.