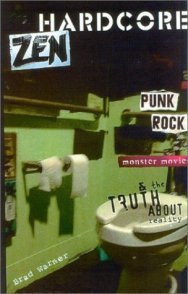

Punk Rock, Monster Movies, and the Truth about Reality

© 2003 by Brad Warner

Published by: Wisdom Publications 206 pp.

not your grandmother’s zen book

You won’t find Hardcore Zen at the bookstore by looking for a cover with a pretty “Zen” picture. This one is about showing us what we don’t want to see; in keeping with that spirit, the cover features a toilet. Brad Warner uses many expressions of the kind which Captain Kirk described as “colorful metaphors” in Star Trek IV, some of which are really striking, “like a pit bull [on] a postman’s ass,” to quote Brad. This ain’t your grandma’s Zen book.

A friend asked me a couple of years ago what I found so valuable about Buddhism, and I replied that Buddhism seemed obsessed with reality. Brad seems to agree, and the difference between reality and “religion” is a running theme throughout the book.

Brad is a married American Zen priest living and teaching in Tokyo, whose day job is making Ultraman monster movies. In keeping with that theme of learning from reality, Brad teaches Zen from his own life, and the book is about one-third autobiography, and two-thirds hard-hitting Zen lessons. He discovered Zen while a punk-rock musician studying at Kent State University (at the same time I was there, BTW). From there he went to Japan, and found employment in making cheesy monster movies, a Soto Zen master, and a wife. Hmm, did I say hard-hitting? Isn’t Zen supposed to be something like a spacious room covered with floor cushions, perfumed with incense, New Age music rippling through the air, and a copy of The Art of Tea on the coffee table? No, it isn’t; It’s about discovering your true nature, and Brad’s mission is to shock us into realizing how desperately we avoid our reality, even with most of what we consider “spirituality.”

Hardcore Zen does have some flaws. Sometimes Brad seems to condemn whatever awakening experiences and traditions which are not like the Zen ideal. My suspicion is that although enlightenment is only one thing, all who experience it do so differently, and will use different terms to describe it.

a brilliant introduction

But if you can take an occasional jibe to your tradition, you’ll find that Warner Roshi is an excellent teacher. His explication of the Heart Sutra is the best I’ve ever read, and his chapter on the “The World of Demons” by itself is worth much more than the price of the entire book. Brad explains how practicing zazen lifts the lid on the things we’ve tried to hide from ourselves, and often reveals what we didn’t want to see: makyo (our psychological demons). This extremely helpful chapter gives excellent advice on how to cope when we start seeing ourselves as we really are instead of how we’ve told ourselves we are. Beyond that, this chapter also has the most lucid explanation of the “no-self” concept in Zen, which can be helpful even to those who have been practicing Zen for years.

The next chapter, “In My Next Life, I Want to Come Back as a Pair of Lucy Liu’s Panties” (I wonder what his wife thinks of that title!) follows, with the clearest explanation I’ve ever seen on how the Buddhist concept of rebirth differs significantly from the general idea of reincarnation. Brad shows how our concepts of the afterlife are usually far off the mark because we don’t understand this present life, which happens in the present moment.

“No Sex with Cantaloupes” (great chapter titles, huh?) is a delightful perspective on personal and social Buddhist morality through the ten training precepts, with an emphasis on its importance: “There are nitwits out there who’ll tell you Buddhism, particularly Zen Buddhism, isn’t concerned with morality, that it’s enlightenment that really counts. They’re wrong. Enlightenment is crap. Living morally and ethically is what really matters.”

That leads into another “hardcore” message: the waste of searching for “enlightenment.” Soon after I realized that enlightenment is real, and there actually are people who maintain a constant awareness of non-duality, I succumbed to the disease of enlightenment-seeking, and from which my own teacher had been trying to cure me. Something clicked in me when reading this:

Zazen isn’t about blissing out or going into an alpha brain-wave trance. It’s about facing who and what you really are, every single goddamn moment. And you aren’t bliss, I’ll tell you that right now. You’re a mess. We all are. But here’s the thing. That mess is itself enlightenment. You’ll eventually see that the “you” that’s a mess isn’t really “you” at all. But whether you notice your own enlightenment or not is entirely inconsequential. Whether you think of yourself as enlightened or not has nothing to do with the real state of affairs.

This is an extremely important point which all the thousands of enlightenment seekers in the world would do well to take to heart. The bottom line, Brad says, is that reality is real. Enlightenment isn’t escaping from it, but going into it, and finding the treasure inside every part and every moment. Hardcore Zen ends with a compelling appeal to practice zazen, the concentrated practice of looking at reality. Zazen can change us, and the world, from within, by destroying the self-interest that comes with the myth of self. He closes with some clear, simple instructions for beginning Zen meditation, written with the confidence of a master who has himself been transformed by this practice.