Ah, so I got your attention! Yesterday, I wrote my first poem in Esperanto… unfortunately, I neglected to save it on my computer, and when my machine did one of its random reboots, it was lost and I haven’t been able to recover it. However, I wasn’t going to post it, anyway. It was, ahem, a very tantric sort of prayer, very personal, and let’s just say it didn’t hold anything back!

It was born of a powerful impression I had upon awakening, of the union of sexuality and spirituality. I sat in meditation, and while I just focussed on my breathing, the poem, in images and words, impressed itself upon me. It wasn’t marked by really any particularly strong feelings, despite some extremely passionate imagery. Horniness was the metaphor, not the message or the vehicle. (Well, a little bit of the vehicle, but not as much as you’d think.)

Sex is not only the ultimate physically unifying action, it’s also a powerful image of unification. That seems to be where my poem was coming from, the awareness that God/man, heaven/earth, Unmanifest/manifestation, are not separate, not-two, but one, no matter how it appears in this wonderful world of phenomena and differentiation.

Some questions… Did the poem come to me in Esperanto because the relative unfamiliarity of the words in that language gave me more freedom to receive them afresh… getting past decades of hearing them as “bad” words in English? Was my determination beforehand not to post the poem a tacit acknowledgment of a taboo? What is the taboo, and why is it there?

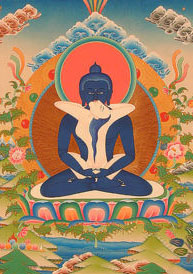

Sexuality and spirituality are considered so distinct, if not opposed, in Western religion, that it’s difficult to imagine them seriously being addressed at once. And Western religion is virtually devoid of images of sacred sexuality, something that I almost don’t notice, until I consider the yab-yum icon of the Buddha simultaneously in mediation and coitus, or the Hindu shivalingam portraying the meeting of God’s feminine and masculine qualities, graphically portrayed as yoni and lingam.

It’s as if in Western religion, the only icon of sacred sex is the hidden icon of man and wife behind closed doors, not to be seen as a whole by anyone but God alone. And even there, the spiritual symbolism is almost never touched upon, despite St. Paul’s teaching that we are the body of Christ, and that God desires for us to be united with him.

Yet to mystics, it occasionally breaks through here and there when allowed, most often in the form of poetry. The Song of Songs is eight chapters of ecstatic holy erotica, but I’m willing to bet you’ve never heard a sermon on it that didn’t bury it under ridiculous layers of symbolism.

The Spanish mystics, Sts. Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross, bring it forth in some of their mystical writings as well. The sculptor Bernini showed that he understood the relationship of Spirit and passion in his wonderful portrayal of “The Ecstasy of St. Teresa,” wherein a key mystical experience of hers is given an undeniably erotic, though modest, treatment.

But the Spanish mystics were talking about spiritual experiences, not sexual ones. What is the place of sex in spirituality? Why have so many mystics for thousands of years, been renunciates? Why is it so often the renunciates who are the ones who elucidate sacred sexuality?

I suspect the reason lies in the tricky nature of desire. Even love is constantly confused with the desire for receiving, and sex is even more prone to seek its own fulfillment. As there is a true love that expects nothing in return, but purely exists to give, there must be a place in sex where you exist solely to give yourself away. In that place, there is nothing that is not God.

In the past, gods demanded blood and bodies. Now, Christ has given his body and blood completely, and you are that.

There. I said it; now let me have it!